It is common knowledge that arts can arouse passions. Some believe that arts should be in school simply because many students thoroughly enjoy them. Others advocate a higher curriculum standing for arts on equal footing with math, science and language arts (Jensen). Now, there is now substantial evidence that arts are a “stand-alone” discipline. I would argue that arts support the neurobiological development of the brain in ways that enhance the social and academic performance of our students. This paper will explore some plausible mechanisms for how that happens.

This article introduces a new way to understand the impact of the arts on our students by asking three questions.

They are:

Question One: What Really Drives Academic Success?

Question Two: Can the Underperforming Brain Be Changed?

Question Three: How Do Arts Change the Brain?

In this article, I’ll asset that a very small group of sub-skills and attitudes drive academic success. I’ll show that brains are highly adaptable and change everyday. Finally, I’ll show that arts may alter the brain in positive ways that no other mediums can do. In sum, arts alter the neurobiological trajectory of the brain in ways that strengthen the academic and social skills unlike any other intervention.

The brain-based approach says, “How does this affect the brain?” The answer is that it’s a powerful positive approach.

Introduction

For students to do well in school, their brain must function in ways that are academically and socially useful. We might loosely organize our students into three groups. There is a group that performs above the mean academically and they socialize reasonably well in a school environment.

Our second group brings special challenges. Students with severe AD/HD, head trauma, genetic disorders, fetal alcohol, oppositional disorders and Asperger’s are just a sampling of the better-known special education challenges educators face today.

Finally, there is a much larger group of students that either underperform and/or misbehave which are given different labels such as unmotivated or “problem students.” This article introduces a novel approach for understanding and succeeding with the last two groups of students. The assertion here is that it is possible to succeed with underperformers with fewer, more targeted interventions, in particular, the arts.

What do the arts bring to the table? The teachers are constantly trying new classroom strategies learned from books, trainings and conferences. The administrators are constantly inspiring, motivating and coaching their staff in endless ways to sharpen their collective “saw.” Unfortunately, this approach of trying to get better performance from students and staff can become overwhelming. There seems to be no limit to the quantity of available strategies, so it becomes very much of a “hit or miss” approach. This results in a dizzying and endless stream of programs, themes, missions, projects and, ultimately, burnout among many educators.

But what if there was another way to go about this process. What if you could do less and get more? That’s what arts do and we’ll explore how that happens. The brain-based approach is a powerful positive approach.

Question One: What Really Drives Academic Success?

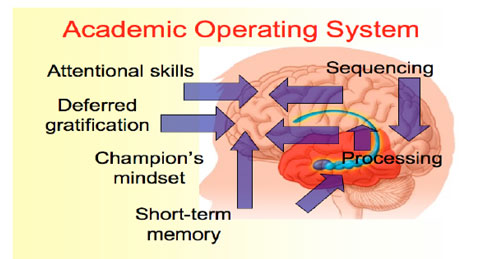

What is actually different in the brain that matters in the school context? I suggest the existence of multiple “operating systems” in the human brain, each of which actually determine success in school. These operating systems (e.g. academic, social, athletic, survival) contribute towards your student’s success. But ultimately, since schools are all expected to reach performance goals, the academic operating system is of most relevance. Understanding this “system” is critical to a school’s success.

The Academic “Operating System”

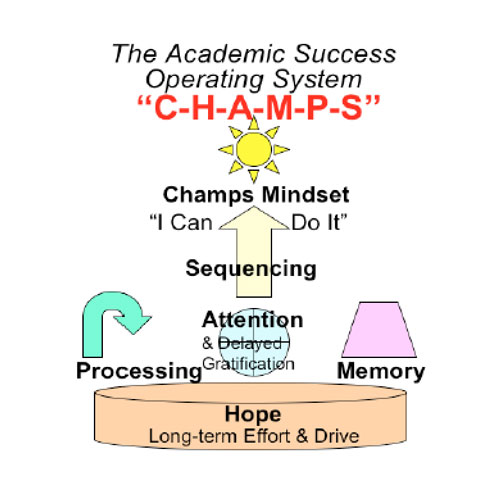

Collectively, we could dream up a list of the mind/brain attributes and the specific skills that students need to have to make it in school. But the list might get a bit cumbersome and, ultimately overwhelming for staff. The “operating system” model attempts to simplify this understanding. We can do that for a good reason. Our brain does not need to be perfect for a student to succeed in school. Academic success does not require perfection and that’s good. School success requires “good enough” and that concept fits better with our brain. The aggregate of these factors is called our academic “operating system”. Among the parts, we might include:

1. Effort: long-term motivation and the ability to defer gratification

2. Processing skills: auditory, visual and tactile

3. Attentional skills: engage, focus and disengage as needed

4. Memory capacity: short term and working memory

5. Sequencing skills: knowing the order of a process

6. Winner’s mindset: “I can do it!” confidence

One does not need to be superior in all of these to get good grades. But one does need enough of each and any compensatory strategies to succeed. We all have a fault-tolerant brain, which is good at compensating and doing “work-arounds” so that one can succeed at a task even if it has to find an unconventional approach to get it done. The good news is that each of the critical processes in the brain’s academic operating system (above) are malleable, trainable and can be improved. To make it more memorable, I have labeled the academic operating system “CHAMPS.”

In this illustration, the six letters of the acronym refer to champion’s mindset, hope, attention, memory, processing and sequencing.

Avoid dismissing this as simply another way to label study skills. While I am a strong supporter of learn to learn skills, this operating system approach describes the deeper neuropsychological underpinnings of academic success. After years of working with students teaching study skills, special education programs and mind/brain processes, what has emerged is a model featuring the fewest “moving parts” needed for school success. The attraction of this model is that it is simple enough for educators to understand, use and modify as needed. More importantly, it is based on a very powerful discovery in recent neuroscience: our brains have significant plasticity (Green CS, and Bavelier D., 2008).

See illustration below:

I assert that students who do well in school have a strong academic operating system. While it does not need to be perfect, there is a threshold that, when reached, ensures academic success. But before we explore it in more detail, is this discussion even relevant? Can the brain change? The brain-based approach says, “Of course that brain can change; it’s designed to do that!”

Question Two: Can the Underperforming Brain Be Changed?

One of the most astonishing developments in cognitive science of the last hundred years is the debunking of the “fixed brain” myth. We now know that brain changes daily. The concept of brain plasticity reminds us that students are not stuck the way they are. While their success is dependent on their “operating systems”, those systems can be upgraded.

We can increase mass in the student’s brain (Dragons and May, 2008) and boost the student’s production of new brain cells (Pereira, et al. 2007) and that’s highly correlated with learning, mood and memory. We can add mass through effective vocabulary instruction (Lee, et al. 2007). When we teach thinking and processing skills, and it alters the brain (Levy (2007). Playing certain computer-aided instructional programs can increase attention and improve working memory, in just several weeks, (Kerns et al. 1999 and Klingberg, et al. 2005), both of which are significant “upgrades” to the student’s operating system.

There are many things that effective schools do well. Whatever you’ve done in the past that worked for students, in some way, it has successfully changed the brain in ways that can be measured on achievement tests. Indirectly, we change the student’s brains at school. When we teach students how to play an instrument, it changes brain mass (Gasser C, Shag G (2003). Many arts can improve attentional and cognitive skills (Gazzaniga, 2008). Playing chess can increase reading (Margulies, 1991) and math (Cage and Smith, 2000) vis a vis the pathways that increase attention, motivation, processing and sequencing skills.

The human brain is highly susceptible to environmental input. In some cases, change can happen, even permanent change, within minutes. But that’s likely to be a change induced through trauma (emotional, psychological or physical). That change takes little time and can be quite lasting, but it’s a negative change.

To get lasting positive change, you’ll want skill-building because it is targeted towards the needs of the operating system. Each day, because learning consumes resources (e.g. glucose, time) there are upper limits on how much change per day. Go right up to the maximum allowable time per day by the brain. On average, that time is about 30-90 minutes of intensive skill building in any area. Beyond that, there’s no evidence of gain. The brain just overloads and the change is dismissed. But a good arts program physically changes the brain. Good schooling has “upgraded” the student’s operating system. In fact, every successful school intervention features a variation on the theme of “rebuild the operating system.”

This system works on the principle of “fewest processes that matter most” to the learning process. But if you simply try to cram more content into the same brain, without “upgrading” the operating system, students will get bored, frustrated, and fail. This is where the arts come in.

Question Three: How Do Arts Change the Brain?

Five universities were funded as part of the Dan Foundation efforts to discover the effects of art on the human brain. Preliminary data after five years shows that arts positively impacts cognition (Posner, et al. 2008) Learning to play music is the best studied of the arts. New evidence suggests that music enhances cognition (Jonides, 2008). There is evidence from top neuroscientists in peer-reviewed journals such as The Journal of Neuroscience. The title, “Musical training shapes structural brain development” gives you a sense of the straightforward evidence (Hyde et. al. 2009). In fact, the brain-based approach says, all arts can affect the brain.

Here’s the significance of a quality academic operating system: it has the capacity to override the adverse risk factors of injuries, toxins, divorce, poverty or a substandard childhood! When this operating system is “off” or simply not up to the constraints and demands of school, students struggle. These are not simple study skills; these are the capacity to focus, capture and discriminate information, process it, remember and represent it in a meaningful way. This bundled set of skills can be more than a great equalizer; it can be a critical piece of your school strategy for academic success with low- income students. When you address academic problems, it will always come back to strengthening the student’s academic operating system. Stronger systems mean better performance.

Arts Build the Operating System

You can build the academic operating system with strategies that strengthen any of the subsystems that make up the academic operating system.

Champion’s Mindset – This is the way of thinking that exudes confidence and willingness to try challenging tasks. Arts provide students ways to succeed as well as ways to showcase their skills. While it’s tough for a language arts or science student to gain public acclaim, artists may develop positive mindsets through stage, concerts, productions, film and dance. Arts give students genuine affirmations often and support well-deserved student-to-student affirmations, too. Provide support for learning with tools, partners and confidence. Create short assignments and quick opportunities for quick successes that tell the learner, “You can do it!” Help strengthen their social status by providing appropriate opportunities for privileges with their peers. This attitude can be trained and it does change the brain (Duerden and Laverdure-Dupont 2008).

Hope – This is the feeling that long-term; it’s worth “staying at it.” It requires deferred gratification and only works when there is something to be hopeful for. Hope is the voice that says to you, “There are better days ahead.” It is fundamental for long-term effort. Arts are not a “quick fix” and typically take months and years to develop significant strengths. This builds confidence and hope. Arts help strengthen teacher-to- student relationships so students know they have social support. Arts help set up situations where students can experience success. Arts provide quality role models or success. Arts teach imagination, positive goal setting and goal-getting. Arts help students learn to manage their time, create checklists to manage their lives. Arts teach how to make better choices and give practice in making choices. Arts invite dreams and let students draw, sing, talk, write or rap about them. Students with learned helplessness have a complete lack of hope, as do many with learning delays but not with arts. The skills of optimism are powerful and can be taught (Seligman 1998).

Attentional skills – Paying attention is not an innate skill. What’s innate is shifting attention from one novel attention-grabber to another. It takes practice to learn to focus on the details over time. Arts training show that perception and sensory awareness can be enhanced (Ahissar, M. (2001) as can attentional skills (Hayes et al. 2003 and Eldar, et al. 2008). Focusing on high-interest content in arts where students can immerse themselves in a situation required detailed focus. Arts build focus through very high interest reading.

Arts build attention through focused practice in martial arts, dance, chess, model building and sports. Students with attention deficit typically have focus and attention issues (along with others), but arts can develop attentional skills. . Students are not stuck with poor attention span. Instead of demanding more attention in class, train students in how to build it.

Arts can make that happen; that’s the brain-based approach.

Memory – In school, a strong memory is not just expected, it is priceless. We are all born with a good long-term memory for our “survival memories” such as where we live and work. We remember much of our spatial learning, emotional events, procedural and skill learning, conditioned response learning and highly behaviorally relevant data such as the names of our siblings, parents and cell number. Outside of those, school learning requires both short-term memory and long-term faculties. Music training strengthens verbal memory (Ho, et al. 2003). Dance strengthens sound and kinesthetic memory. Practice with simple call response in class. Build up to pair-share with partners. Strengthen memory with repetition, framing the importance of an idea. Develop their skills in mind mapping. This system can be enhanced through practice in many ways (Jaeggi et al.,2008).

Processing – This is the capacity to “flesh out” something. At the micro level, it means a student can process auditory input such as phonemes. That’s quite important for reading. At the more macro level, it means the capacity to “process” an event such as being called a name, breaking up with a lover or forgetting to do your homework. We all need to know how to deal with difficulties, particularly emotional ones.

In addition, we need to be able to ask appropriate questions and think critically about a problem. We now know that the arts support math and science, two areas where processing is critical (Spelke, E. (2008). Arts provide the “how to” of processes because teachers either allow you to learn on your own or they walk you through steps. “Now we are doing this… and next we’ll need to…” In other subjects, teachers often tell students what to do, but not how to do it. Arts can offer challenging games with structured practice time. Arts strengthen processing when students learn to play a musical instrument, design visual portfolios or take drama classes. Fortunately their brains can change when their system is targeted and treated. (Gaab, et al., 2007) and Erickson et al., 2007)

Sequencing – This is the set of skills that allows us to prioritize, identify and put in order a set of actions. When you cook and prepare a meal for guests, pack for a trip or paint a bedroom, you need sequencing skills. At school kids need sequencing for starting homework, writing a paper and planning a project. They need it for conflict resolution, doing a math problem or planning their day. We now know that arts support reading skills (Wandell, B., et al. 2008). In addition to dance, music playing can also strengthen both tactile and auditory memory (Ragert et al. 2004). All music requires and develops sequencing skills. Even the visual artist has to sequence the thinking, the shapes, proportions color and contrast. Visual arts give students the opportunity for building things (assembling models, paper projects or project displays). Be the guide for their time invested in organizing their work, writing a paper or problem solving. Most art opportunities build and strengthen attention, hope, processing, and sequencing. This is a skill set than can change through practice.

How to Maximize Results

Building the operating system is a top priority. If a student is in an impoverished environment for hours at home a day, then gets a few minutes of operating system enhancement at school, that time constitutes only a tiny fragment of the student’s total week. That time is unlikely to produce substantial long-term benefits, though it’s certainly better than nothing. The message her is clear: do not kid yourself about changing the brain: it takes focused effort over time. To get lasting positive change, you’ll want to go right up to the maximum allowable time per day by the brain. On average, that time is about 30-90 minutes of arts will build a student’s operating system. Beyond that, there’s no evidence of gain. The brain just overloads and the change is dismissed.

Let’s translate this into your school time. To maximize change with the arts in mind, it’s got to be a priority. Unless one follows the “brain’s rules” for skill-building, precious time is wasted, students learn less and teachers get frustrated. The rules are simple. The learner must buy into the activity, perceive relevance, pay focused attention and get enough rest at night. The actual activity must be coherent, have built-in positive and negative feedback, last at least 30-90 minutes a day as well as for 3-6 days a week. If you don’t follow the rules, your results will be delayed. Arts are one of the best options for building the operating system. When we lose out on arts, we lose out on more than student enjoyment or potential career options. We lose out on the critical brain development for immediate academic success and lifelong learning.

Summary

The brain-based approach says, “How does music affect the brain?” The answer is that it’s a powerful positive approach.

We explored three questions.

The first question asked us, “What Really Drives Academic Success?” This question was addressed by suggesting that six factors comprise an “academic operating system” and that they matter more than anything else within our brain. While we have other, parallel “operating systems, the academic one is a big piece of the achievement score solution.

Question two was, “Can the Underperforming Brain Be Changed?” Yes, it can! The scientific evidence shows that it can be changed. Of particular interest is that studies show the academic operating system can be strengthened with targeted skill-building.

Our third question was, “How Do Arts Change the Brain?” By using the operating system as a vehicle for progress, arts give students a practical path for success. Only a few things really matter. Those few things can be improved with targeted practice. Arts are a formidable resource for building the student’s operating system. But now, we have to put it in action. Support the arts for any reason you want. But arts can and do hold their own when it comes to improving the lives of our students.

All aboard?

Eric Jensen is a former teacher at all levels, including three universities. He co-founded Jensen Learning Corporation, an international professional training organization that synthesizes brain research and its applications for educators (www.jensenlearning.com). Jensen is a member of the International Society for Neuroscience, New York Academy of Science and is has a PhD in Human Development. Jensen has authored over 25 books including Arts with the Brain in Mind, Teaching with the Brain in Mind, Different Brains, Different Learners and Enriching the Brain. He can be reached at info@jensenlearning.com.

While there are many unique mental health resources available, none of them are comprehensive and specifically tailored to the physically disabled. After research across the resources available on the web, the AAC team noticed the absence of a centralized resource designed to help understand the basics of mental health, alcohol use and addiction within this demographic and offer guidance on navigating support systems.

They decided to fill this gap of knowledge. The result is this page: http://sunrisehouse.com/addiction-demographics/physically-disabled/

This page summarizes available governmental, organizational and other resources and makes them easily accessible to those searching for assistance. It includes dozens of the latest studies and external resources for the physically disabled seeking assistance.

References

Ahissar, M. (2001). Perceptual training: A tool for both modifying the brain and exploring it. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98: 11842-11843

Alain C, Snyder JS, He Y, Reinke KS. (2007) Changes in auditory cortex parallel rapid perceptual learning. Cereb Cortex. May;17(5):1074-84.

Bengtsson SL, Nagy Z, Skare S, et al. (2005) Extensive piano practicing has regionally specific effects on white matter development. Nat Neuroscience;8:1148–50.

Cage, B., James Smith. (2000) “The Effects of Chess Instruction on Mathematics Achievement of Southern, Rural, Black, Secondary Students”, Research in the Schools vol 7n1p19-26 Spr.

Draganski B, Gaser C, Busch V, Schuierer G, Bogdahn U, May A (2004) Neuroplasticity: changes in grey matter induced by training. Nature 427:311–312

Draganski B, Gaser C, Kempermann G, Kuhn HG, Winkler J, Büchel C, May A. (2006) Temporal and spatial dynamics of brain structure changes during extensive learning. J Neurosci. 2006 Jun 7;26(23):6314-7.

Draganski B, May A. (2008) Training-induced structural changes in the adult human brain. Behav Brain Res. 2008 Sep 1;192(1):137-42.

Duerden, E.D. and D. Laverdure-Dupont (2008) Practice Makes Cortex J. Neurosci., August 27; 28(35): 8655 – 8657.

Eldar S, Ricon T, Bar-Haim Y. (2008) Plasticity in attention: implications for stress response in children. Behav Res Ther. Apr;46(4):450-61.

Erickson KI, Colcombe SJ, Wadhwa R, Bherer L, Peterson MS, Scalf PE, Kim JS, Alvarado M, Kramer AF. (2007) Training-induced functional activation changes in dual-task processing: an FMRI study. Cereb Cortex. Jan;17(1):192-204.

Ferrer E, McArdle JJ, Shaywitz BA, Holahan JM, Marchione K, Shaywitz SE. (2007) Longitudinal models of developmental dynamics between reading and cognition from childhood to adolescence. Dev Psychol. 2007 Nov;43(6):1460-73

Gaab, N., Gabrieli, J. D., Deutsch, G. K., Tallal, P., & Temple E. (2007). Neural correlates of rapid auditory processing are disrupted in children with developmental dyslexia and ameliorated with training: an fMRI study. Neurological Neuroscience. 25(3-4), 295-310.

Gaser C, Schlaug G (2003) Brain structures differ between musicians and non-musicians. J Neurosci 23:9240–924

Green CS, Bavelier D. (2008) Exercising your brain: a review of human brain plasticity and training- induced learning. Psychol Aging. Dec;23(4):692-701.

Ho YC, Cheung MC, Chan AS. (2003) Music training improves verbal but not visual memory: cross- sectional and longitudinal explorations in children. Neuropsychology. 2003 Jul;17(3):439-5.

Hyde KL, Lerch J, Norton A, Forgeard M, Winner E, Evans AC, Schlaug G. (2009) Musical training shapes structural brain development. J Neurosci. Mar 11;29(10):3019-25.

Jaeggi SM, Buschkuehl M, Jonides J, Perrig WJ.(2008) Improving fluid intelligence with training on working memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. May 13;105(19):6829-33

Jensen, E. (2001) Arts with the Brain in Mind. ASCD, Alexandri,a VA.

Jonides, J. (2008) “Musical Skill and Cognition” Pgs. 11-16. In “How Arts Training Influences Cognition” in “Learning, Arts, and the Brain: The Dana Consortium Report on Arts and Cognition” Organized by: Gazzaniga, M., Edited by Asbury, C. and Rich, B. Published by Dana Press. New York/Washington, D.C. web access: www.dana.org.

Kandel DB, Johnson JG, Bird HR, Weissman MM, Goodman SH, Lahey BB, Regier DA, Schwab-Stone ME. (1999) Psychiatric comorbidity among adolescents with substance use disorders: findings from the MECA Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. Jun;38(6):693-9. Recent findings at: http://www.aacap.or /cs/giving;jsessionid=aTayAfGJ00CcpGdBVb

Lee, JH. T. Devlin, C. Shakeshaft, L. H. Stewart, A. Brennan, J. Glensman, K. Pitcher, J. Crinion, A. Mechelli, R. S. J. Frackowiak, Green, DW and Price, CJ. (2007) Anatomical Traces of Vocabulary Acquisition in the Adolescent Brain. J. Neurosci., January 31; 27(5): 1184 – 1189

L.M. Levy (2007) Inducing Brain Growth by Pure Thought: Can Learning and Practice Change the Structure of the Cortex? AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol., November 1; 28(10): 1836 – 1837.

Mazziotta JC, Woods R, Iacoboni M, Sicotte N, Yaden K, Tran M, Bean C, Kaplan J, Toga AW; (2009) The myth of the normal, average human brain–the ICBM experience: (1) subject screening and eligibility. Neuroimage. Feb 1;44(3):914-22

Hayes EA, Warrier CM, Nicol TG, Zecker SG, Kraus N. (2003) Neural plasticity following auditory training in children with learning problems. Clin Neurophysiol. Apr;114(4):673-84.

Ilg, R., A. M. Wohlschlager, C. Gaser, Y. Liebau, R. Dauner, A. Woller, C. Zimmer, J. Zihl, and M. Muhlau (2008) Gray Matter Increase Induced by Practice Correlates with Task-Specific Activation: A Combined Functional and Morphometric Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. J. Neurosci., April 16, 28(16): 4210 – 4215.

Posner, M., Rothbart, MK, Sheese, BK, and Kieras, J. (2008) “How Arts Training Influences Cognition” Pgs. 1-10. in “Learning, Arts, and the Brain: The Dana Consortium Report on Arts and Cognition” Edited by: Gazzaniga, M., Edited by Asbury, C. and Rich, B. Published by Dana Press. New York/Washington, D.C. web access: www.dana.org.

Ragert P, Schmidt A, Altenmüller E, Dinse HR. (2004) Superior tactile performance and learning in professional pianists: evidence for meta-plasticity in musicians. Eur J Neurosci. Jan;19(2):473-8

Seligman, M. (1998) Learned Optimism: How to Change Your Mind and Your Life. Free Press, New York.

Spelke, E. (2008) Effects of Music Instruction on Developing Cognitive Systems at the Foundations of Mathematics and Science. ” Pgs. 17-50 In “How Arts Training Influences Cognition” in “Learning, Arts, and the Brain: The Dana Consortium Report on Arts and Cognition” Organized by: Gazzaniga, M., Edited by Asbury, C. and Rich, B. Published by Dana Press. New York/Washington, D.C. web access: www.dana.org.

Wandell, B., Dougherty, R., Ben-Shachar, M. and Deutsch, G. (2008) Training in the Arts, Reading, and Brain Imaging. Pgs. 51-60 In “How Arts Training Influences Cognition” in “Learning, Arts, and the Brain: The Dana Consortium Report on Arts and Cognition” Organized by: Gazzaniga, M., Edited by Asbury, C. and Rich, B. Published by Dana Press. New York/Washington, D.C. web access: www.dana.org.

Iliana Aljure

Dr. Jensen:

Considering my field of interest is teaching the arts, and particularly dance, for the last 25 years of my life, this article is a ground breaking summary on the importance of the arts in a school environment. I have dedicated my life to understand its benefits as a separate academic subject and my thesis when I graduated from New York University in Dance Education, was exactly this. Through interviews, questionaries and other inquiry sources with my students, I found much more answers on why kids love the arts, such as a sense of winning, social bonding, emotional awareness, collaboration and cooperation, team building, growing self esteem, love and belonging, power and recognition, freedom, joy of learning and the sense of being part of of project that changed the school environment.

For my thesis, I discovered many books that helped me discover the wonders of teaching the arts, books I will share with the brain based community in this website. One of them particularly, was the center of my study: CHANGING SCHOOLS THROUGH THE ARTS by Jane Remer, published by the American Council for the Arts. I highly recommend this book for anyone interested in the field.

Thanks for an amazing article and for the book you wrote on the field ARTS WITH THE BRAIN IN MIND, which is a constant source in my night table!

¿May I translate and publish this article for our school magazine called ROCHESTEM?

Iliana Aljure

Eric Jensen

May I translate and publish this article for our school magazine called ROCHESTEM?

Of course you may Iliana,

Eric