Teacher readiness series #3

I’m not nearly as concerned about student readiness for school as I am about teacher readiness. One of the experiences that we have all shared at some point as students is the teacher that thinks they will prevail in managing their classroom through many words. “Class, be quiet. Devon please, I am trying to teach here. Courtney, Courtney, Courtney. No, no Reese put that down. CLASS….” and so on. We all have fallen prey to the Peanuts syndrome. That is where we have said so much, that no matter what we say, it all sounds like “Blah, blah, blah, blah, blah…..” to the students. At a certain point, it begins to not matter at all what you say, the students are simply reading your emotional level and making sure you are slightly under the EXPLODE level. Most of us, if we were honest don’t like living slightly under the EXPLODE level for even a few moments every day.

Working memory, as we have discussed, only has a certain number of slots for students to hold information in and work with it. That means if we say too much, our words will do one of two things. Either they will bounce off the student and not be heard, or they will replace some information we want the student to be working with and they won’t remember it. How do we begin to rescue ourselves from the Peanut’s Syndrome in managing our students? One of the best places to start is in giving directions.

If working memory is limited in capacity, then we will be most successful by giving one direction at a time (or as few as possible), and allowing the students some working memory room to take that direction and be able to figure out what is needed to complete it. The direction itself should be as short and succinct as possible, providing lots of meaning in as few words as possible. We should also think about what it takes to complete a task. To say “Okay everyone, let’s get ready for recess” could mean different things to different kids unless there has been a lot of training. One student may actually put things away, while his neighbor begins bouncing off the walls because that sounds like a recess ready activity.

Rather than an indistinct direction, be very specific. 1) “Class please close your books and look at me.” When you have everyone’s eyes, 2) “When I say go, please quietly put your book away at the book center and then line up by the door…Go!“ As they begin to move, look for someone following the directions and say, “Great job Carson! You put your book away and are standing quietly by the door.” 3) “Please quiet down and make sure the line is straight. In a moment, when I say go, we will walk in an orderly line to the playground.” 4) When they are quiet and straight, say “Go!” and begin walking. Note that it helps to use a cue word like “go” to begin the activity. This makes sure that everyone waits and listens to your directions before they start.

Early in the year, it helps to teach and demonstrate what you mean by an orderly line. “Reggie what does it look like to walk in an orderly line? That’s right, cotton ball feet ready, lips zipped, and hands to ourselves. Thank you for showing us. Emily what happens if we are not orderly?” “Yes Emily, we will come back to the classroom and begin again. You have a choice, either you can walk in an orderly line to the playground and play, or we can practice walking in an orderly line until you get it right. It’s your choice.”

To give good directions requires thinking through the process, breaking down the steps, giving the directions step by step, training with demonstration when necessary to make sure students understand each step, and waiting for the completion of each step. If you do this, you will find you actually use less time than giving multiple steps at once.

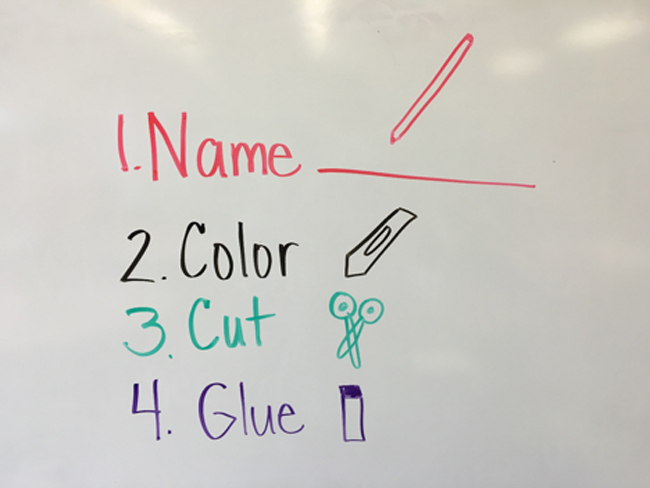

What about giving a multiple step assignment so that you can move through the classroom and assist students while they work through the process? In that case write the directions on the board in their simplest possible statement using colors and symbols, and train the students what each step means over time. Consider the following set of instructions written on the board:

Note that for ease of reference each instruction is simple, has a number, a color, and a symbol. This approach allows you to direct a class that may not have readers, or who have learning disabilities that are often aided by color. If Kailey is not a reader, doesn’t know her numbers, has just finished coloring and doesn’t know what to do next, you can ask her what she just completed. Kailey responds hesitantly “Coloring”. “Good Kailey which color is the crayon?” Kailey responds with a guessing voice, “Black?” Yes Kailey and what picture is under the crayon in green? “Ummmmm, scissors?” she says hopefully. “It’s the scissors, isn’t it? We cut next. Remember how I taught you to cut? All right hold those scissors and move that paper to cut out the turtle.”

Learning how to give effective directions is a certain route to learning how to use less words with more meaning. This approach will help your students use their working memory effectively becoming more successful in your classroom.